Know the Basics: Henrik Ibsen

Written by Ashleigh Gardner

February 21, 2019

Practically every professional theatre in the nation is doing Lucas Hnath’s hit play A Doll’s House, Part 2 and for good reason! It got eight Tony nominations in 2017. But before you embark on a mission to see Hnath’s seriocomedy, start out by exploring Henrik Ibsen, the playwright of the original story and the father of realism in theatre.

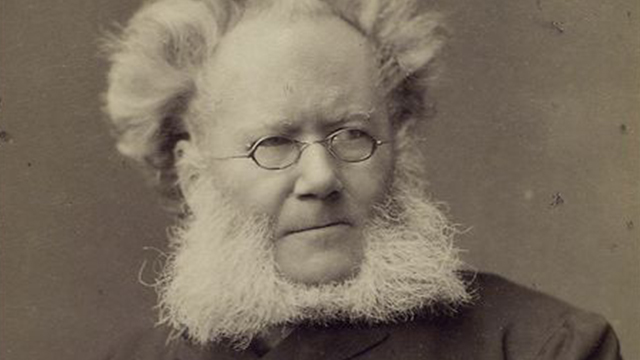

Who is Henrik Ibsen?

The illustrious Henrik Johan Ibsen was a Norwegian playwright, director, and poet. Born in Skein in Telemark, Norway on March 20, 1828, Ibsen was the son of well-respected parents of the merchant class (think of them as middle-class today). His parents were also distantly related, and he found this semi-incestuous relationship interesting enough to talk about the concept in one of his most famous plays, Ghosts.

When Ibsen was 22, he wrote his first play, Catilina (1850), and it was published under his pseudonym, “Brynjolf Bjarme”. Sadly, it was never performed. His luck with productions was further daunted when his play The Burial Mound (1850) was staged but was unsuccessful. Even though he encountered a lot of setbacks, he was still determined to become a playwright, and so he got a job at Det norske Theater in Bergen, Norway, where he was involved with more than 145 plays as a producer, director, and playwright. However, this success didn’t last long. He became disillusioned with Norwegian life, especially while living in near poverty, and after his marriage and birth of his first child, he left Norway for Italy, and he didn’t return to his home country for 27 years.

But when he did return, he began writing and producing works that challenged how plays were written, how drama addressed social issues, and how those social issues were experienced by the Norwegian middle class.

Why’s he so important?

Brace yourselves. Ibsen is the father of realism in theatre. Before Ibsen, theatre was looked at as entertainment rather than a legitimate art form. But when an audience went to the theatre to watch an Ibsen play, they were in for a rollercoaster of a night. Plays like A Doll’s House, Hedda Gabler, The Master Builder, An Enemy of the People, and Ghosts tackled extreme (for those days) social issues like a woman choosing herself over her husband and family (A Doll’s House); business ethics (A Master Builder); mental illness (Hedda Gabler); adultery and syphilis (An Enemy of the People); and venereal disease, incest, and euthanasia (Ghosts).

The theatre-going public went bonkers after they saw A Doll’s House because “how could a woman leave her family!?” The thing with Ibsen, though, was that he intended to upset his audiences. His thought process was this: how can things get better if we don’t talk about them? Ibsen wrote for the middle-class because he was tired of sweeping social issues under the rug. Fun fact: A Doll’s House was actually based on an event in Ibsen’s own life. Laura Keiler, a friend of Ibsen’s, ask him for a loan. When he refused, she went to a lender and illegally borrowed money and forged a check so that she could take her ailing husband to Italy to recuperate. When her husband found out and became furious, he demanded a divorce. Laura had a nervous breakdown and went to an asylum for a month. She and her husband later got back together, and Laura never forgave Ibsen for using her life as a basis for his drama. (She went on to become a novelist! Fancy that!)

Brand (1866)

A play written in verse, Brand is the story of a priest who wishes to live his life as honestly as he can, refusing to take compromises. However, his belief system and actions ultimately leave him alone as a lonely idealist whose only mission is to right the world by whatever judgement he deems necessary.

A Doll’s House (1879)

Quite possibly Ibsen’s most famous work, A Doll’s House centers around Nora Helmer, a woman who is a different person to different people, and her strict and uptight husband, Torvald. They have a seemingly perfect marriage, but under the surface, a secret is killing them. Over the course of the play, we learn that Nora has committed fraud by forging her father’s signature on a loan, and Krogstad, the banker with whom she did business, threatens her with blackmail. When he reveals to Torvald what Nora has done, Torvald explodes in a flurry of anger and fear, and it is then that Nora realizes that her husband is not the man she thought he was. When Nora walks out of the house for the last time, it is known as “the door slam heard round the world.” A Doll’s House explores concepts of the self: who are we to others? who are we by ourselves? what kind of masks do we put on for the sake of others’ benefit?

Ghosts (1881)

Mrs. Alving’s marriage to her husband, Captain Alving, was a miserable one, and her son, Oswald, has inherited syphilis because of his father’s philandering. As she tries to open an orphanage with the money her husband left her, she encounters frustrating roadblocks along the way. Additionally, Oswald has fallen in love with Regina, the maid, who also is secretly Captain Alving’s illegitimate daughter — making Oswald and Regina half-siblings. On top of everything else, Oswald has asked his mother to end his life via a morphine overdose because his illness is getting progressively worse, leaving Mrs. Alving with the choice to kill her ailing son and relieve him of pain or allow him to continue living in agony. A harsh commentary on 19th-century morality, Ghosts explores concepts of infidelity in marriage, immorality, and incest.

Rosmersholm (1886)

After the suicide of his wife, Beata, Rosmer invites a young woman named Rebecca to stay in the family home (Rebecca had moved in as a friend of Beata before Beata’s death). His relationship with her is romantic, though he insists that it is strictly platonic. After he is publicly criticized for his political leanings and his relationship with Rebecca is outed, he begins to blame himself for his wife’s suicide (Beata jumped to her death from a cliff). In a twist, Rebecca confesses that she drove Beata to kill herself so that Rosmer would find comfort in Rebecca. Rosmersholm is a bleak but gripping drama about family ethics and the power of suggestion.

Hedda Gabler (1890)

The daughter of an aristocratic general, Hedda has just returned to her home from her honeymoon with her husband, George Tesman. It becomes abundantly clear over the course of the play that Hedda does not love George, and it is revealed that she has had a relationship in the past with George’s academic rival, Eilert, who now has a relationship with Hedda’s friend, Thea. Hedda’s mental state, disrupted by her jealousy of Thea and Eilert and her love-barren marriage, begins to deteriorate. She encourages Eilert to kill himself, giving him a pistol, and when Eilert is found dead in a brothel, Judge Brack threatens to blackmail Hedda. She then commits the ultimate and most desperate act of escape: suicide.

Interested in theatre history? Check out our other features below!

- 25 Plays all High School Seniors Should Read (Before They Graduate)

- 10 Contemporary LGBT Playwrights You Should Know

- 10 Contemporary Native American Playwrights You Should Know

- 10 Contemporary Playwrights of Color You Should Know

- 10 Asian American Playwrights You Should Know

- 10 Latinx, Hispanic, and Chicano/a Playwrights You Should Know

- 10 Eighteenth-Century Female Playwrights You Should Know

- 10 Nineteenth-Century Female Playwrights You Should Know

- 10 Classic Russian Playwrights You Should Know

- 12 Elizabethan and Jacobean Playwrights You Should Know

- 7 Greek and Roman Playwrights You Should Know

- 13 Classic American Playwrights You Should Know

- Early 20th Century Broadway Composers and Lyricists You Should Know