12 Ways Taking A Playwrighting Course Changed My Life

Written by Tatiana Rodriguez

September 14, 2017

Before going to college, playwrighting felt more like a hobby to me. I used my vague understanding of its form to create stories I wanted to share with my friends, family and the people around me. Years later, in a college setting, I learned from my professors and mentors how important playwrighting and creating is to the theatre community. Within its many layers, playwrighting has the power to engage, to create conversation, to share testimony, and to cultivate craft. In celebration of such, here are 12 lessons I learned while taking a playwrighting course and how they changed my life as a writer.

1. I developed a better understanding and appreciation for the craft of playwrighting.

The act of playwrighting isn’t about putting words on paper. It’s a process that requires time, practice and diligence, the same way all great crafts do. In order to equip yourself as a playwright, you should take the time to learn about the many different facets of storytelling and how playwrighting has evolved from such.

2. I learned that in order to evolve your script, you first have to evolve your characters.

Yes, the plot is important, but knowing your characters is, too. It’s essential that you know the ways in which your characters react within their world. Once you’ve taken the time to establish their personalities and attributes, you can more easily develop their stories.

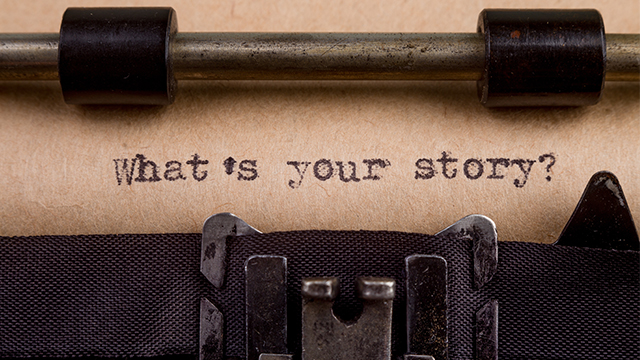

3. The act of storytelling comes in a multitude of perspectives (what’s important is to find yours).

There will always be other playwrights who seem more established, whose perspectives are distinct, or are more developed. But rather than compare your work to that of others, take the time to embrace your own perspective.

4. You should always take the time to read your work out loud.

Whether it’s dialogue, stage directions, or imagery — make sure you read your work out loud. You’ll catch grammar mistakes, spelling errors, and perfunctory flaws. It will allow you the chance to establish your flow, and it’ll help immensely in regards to writing a naturally occurring dialogue.

5. While detail is important, it’s also important not to overcomplicate.

Detail ≠ overcomplicating your work. It’s about choosing the right words, finding the right breaks, recognizing that a scene is lagging, and should be re-worked or cut down, instead of trying to rejuvenate it with more text.

6. There will be times when you need to take breaks and times when you’ll need to push through.

This can be difficult for those who fancy themselves as self-motivators. In times of struggle it is important to recognize when you need to keep writing or simply take a break. Use your instincts to realize what is best for you and your art.

7. When in doubt, do not be afraid to workshop (it out).

Workshops are a great place for you to gain outside perspective on your work. It’s one of the few places you can receive feedback from fellow writers and peers without feeling the pressure to present a completed piece of work.

8. The allocation of time is the allocation of will power.

Writing is a process. It takes time to get into your creative headspace, to write a scene, to edit and revise. So in order to do it properly, you’ll need to set aside time. You are only going to get done the amount in which you allow yourself to.

9. If you’re struggling to put your thoughts into words, perhaps you need to try a different medium.

Do not be afraid of using other artistic mediums to get yourself out of a writer’s block. Create a collage, sketch or paint a picture, move your body and dance, until the emotion in which you are trying to capture fills your subconscious. Then, let your mind do the rest.

10. Receiving critique is inevitable but what you do with it is not, it’s all up to you.

It’s imperative that you learn how to take critique, it’s what will allow you to develop your technique and think more critically about your work. But you do not have to take every critique and apply it to your work. As the writer you get to choose what changes work and what changes do not.

11. Sometimes your best idea is the one you didn’t mean to write.

Perhaps you wrote a poem, a short story, an essay. Perhaps you’ve been doing a lot of research about a subject in which you find incredibly interesting — suddenly you’re imagining what it would look like on stage. Your best ideas are often the ones you do not have to force.

12. Vulnerability is part of the craft.

Let your creativity expand farther than you ever imagined. Do not let the fear of failure or the fear of facing hardship and criticism stand in the way of your art. That thing you are afraid to write — write that.

Need some advice? We’ve got you covered.

- How to Bow (And What Your Bow Says About You)

- 10 Basic Rules of Stage Combat (That Keep Everyone Safe)

- 5 Advantages of Learning Stage Combat

- Don’t Be a Diva: Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

- 9 Articles of Clothing Every Thespian Should Keep In Their Wardrobe

- What Makes an Actor Website WOW?

- “Is my attitude not getting me roles?” And Other Essential Questions for Actors

- 6 Steps to Memorizing Shakespeare

- 10 Tricks to Staying Healthy All Season Long

- What Does It Take to Break Into Voiceovers?

- 5 Tips for Nailing Your College Music Theatre Audition

- 10 Tips on Owning the Room at Competition

- How to Balance Theatre and Coursework

- The 10 Secrets of Great Understudying

- 10 Items Every Actor Should Carry in Their Rehearsal Bag

- 10 Items Every Dancer Should Keep in Their Rehearsal Bag