Devising Theatre: 7 Quick Tips for Your First Devising Project

Written by Ashleigh Gardner

November 14, 2018

If you’re thinking of creating a devised theatre piece, take a look at the suggestions below.

1. What is devising?

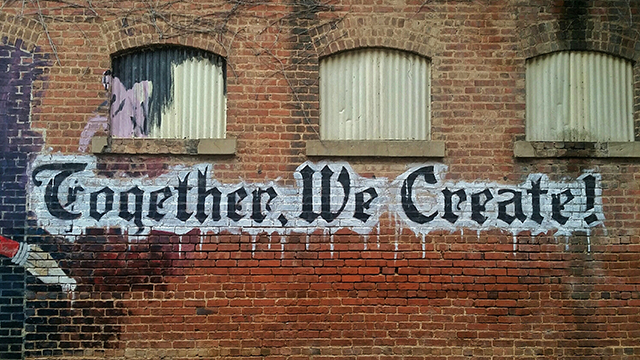

“Devising” is a process in which the entire creative team of a show develops a show collaboratively. Sometimes, there isn’t even a script to begin with (in this case, a script may be written based on improvised scenes), and sometimes there is a script (in this case, the ensemble and director work together to make decisions regarding blocking, music choices, and/or costume and makeup choices). Creating a devised theatre piece allows creativity to blossom from multiple sources in a space which is usually dominated by a single person: the director. In the case of devising theatre, the director is a facilitator that encourages the birth of ideas from the minds and hearts of actors and designers. It also encourages a higher level of personal investment in the project since so many people’s ideas are present and utilized.

2. Where do I start with a devised piece?

Most devised theatre pieces are about making a show that centers around a larger concept: love, envy, bravery, education, loneliness, family. Devised pieces can be rooted in a story a performer tells during a rehearsal or a news broadcast on television or radio. Improv games, Viewpoints exercises, or group brainstorming are great ways to get some scene ideas in the air.

If your devised theatre piece is based on an already existing text like the Odyssey, a Shakespearean play, or another public domain text, you can use Viewpoints to come up with a few blocking, movement, or sound moments your cast may want to include in the final production.

(You can find the Viewpoints book by Anne Bogart and Tina Landau here.)

3. Understand your source material and be passionate about its themes, messaging, and story.

There’s one thing that’s for certain: it’s always harder to work on a project when you’re not passionate about it. So get passionate! Ask yourself and your collaborators why they care so much about the devised theatre piece they’re creating. How does it resonate within their lives? And if the devised piece is from an existing text, make sure all collaborators are familiar enough with the source material that they can discuss it in depth when necessary. After all, it’s easier to collaborate when everyone is already on the same page.

4. Be open to receiving ideas from everyone.

Sometimes it can be difficult to accept other people’s ideas when they don’t immediately mesh with our own. However, it’s important to remember that everyone comes from different experiences and backgrounds. Someone might bring something to the metaphorical table that may end up being a huge part of the devised piece. For example, a performer may offer up the idea that a tango might work well for one scene, even though ballroom dancing isn’t at all included in any other part of the devised story. This idea may help other performers tap into their own interest in dance, and they might offer up similar ideas (swing dance, foxtrot, waltz) in later devising sessions, culminating in a show that uses ballroom dance to express the personalities of different characters.

5. Don’t throw out anybody’s ideas.

This is a big one. As stated above, it’s important that we keep an open mind when devising theatre, so if an idea doesn’t work out now, keep it in a “bank” for future rehearsals. If a moment onstage isn’t working out, see if you can pull from this “bank” of set-aside ideas. You may be surprised at what works!

6. Remember that everyone works differently.

Not everyone is used to being asked for their ideas or opinions, so don’t be surprised if not everyone speaks up or offers ideas. They may be like me — comfortable being told what’s expected of them onstage and running within those boundaries. Instead of asking people right away what some of their ideas are, ask them to write them down on a piece of paper without their name (many young students are afraid of looking foolish, so this level of anonymity cushions that fear). Then, after reminding all collaborators that the rehearsal process is an open environment, read the papers out loud. Keep all ideas in the “bank”, and move forward with the ideas that feel like the most effective choices at the time. On the other hand, you may have performers that blossom in a devised theatre environment. If this is the case, encourage them to partner up with a performer who isn’t as active so that they can learn from one another.

7. Keep it as positive an environment as possible.

Devised theatre isn’t for everyone, and sometimes coming up with ideas from scratch gets frustrating. Use this as an opportunity to encourage a positive and nurturing environment. Remind performers that nothing has to be perfect, and that the goal of a devised theatre piece is to enjoy the journey as well as the destination.

Need some advice? We’ve got you covered.

- 5 Ways to Say “Thank You” to Your Cast and Crew

- 5 Ways to Take Care of Yourself During Tech Week

- The Room Where It Happens: An Insider’s Guide to the College Audition

- How to Bow (And What Your Bow Says About You)

- 10 Basic Rules of Stage Combat (That Keep Everyone Safe)

- 5 Advantages of Learning Stage Combat

- Don’t Be a Diva: Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

- 9 Articles of Clothing Every Thespian Should Keep In Their Wardrobe

- What Makes an Actor Website WOW?

- “Is my attitude not getting me roles?” And Other Essential Questions for Actors

- 6 Steps to Memorizing Shakespeare

- 10 Tricks to Staying Healthy All Season Long

- What Does It Take to Break Into Voiceovers?

- 5 Tips for Nailing Your College Music Theatre Audition

- 10 Tips on Owning the Room at Competition

- How to Balance Theatre and Coursework

- The 10 Secrets of Great Understudying

- 10 Items Every Actor Should Carry in Their Rehearsal Bag

- 10 Items Every Dancer Should Keep in Their Rehearsal Bag