The Low-Down on Dropping a Record

Written by: Amanda Grace

August 14, 2020

Technically speaking, I’m an incredibly accomplished songwriter. My nine-year career includes three original albums, compositions for shows written by playwrights as varied as Bertolt Brecht and Mac Wellman, and original one-off performances created for cabarets and variety shows.

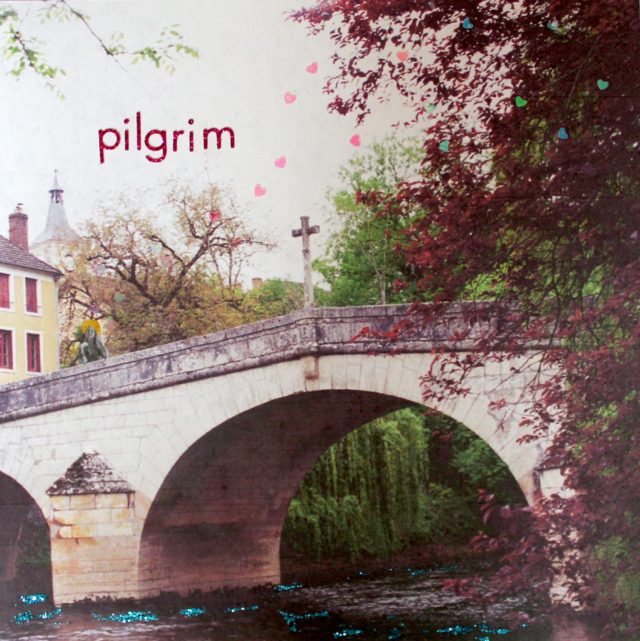

It’s somewhat surreal to think Incommensurable, Millennium, and Pilgrim, bunches of notes I thought up in my little head, have been played on college radio and across continents. I started with a guitar, a ukulele, and a song in my heart. Now my songs play on Spotify, Instagram and Facebook Music, Bandcamp, and iTunes. If you’re a musician and have no idea what you’re doing, great; neither did I when I started. Lucky for you, PerformerStuff has asked me to share the know-how on how to drop a record from start to finish—and I’m nothing if not down to help my friends.

As my creative process has been refined through the years, I’ll expand upon my latest album, Pilgrim, as an example. You can listen to her, and her sister records, in their full finished glory at https://amandagrace.bandcamp.com/.

STEP ONE: Write a bunch of garbage.

The first song you write will be trash. The forty-fifth song you write will probably be trash. But the good songs hide in between, and to get a hit single, you’ve got to go dumpster diving. My best songs tend to come out in one piece, but some have been stitched together from fragments of poetry that bubbled up at all sorts of inconvenient times, so keep everything you write handy until you’re sure it’s not useful.

Every musician has a different process, and various tracks will have different journeys. I tend to settle my lyrics before my scores, and I develop melodies on my voice, which I then figure out how to accompany, as seen in these scribblings for a track called “Una’s Lion.”

Try not to worry about writing the perfect song. I’ve found the tracks that go over best with my audiences tend to be the ones that “wrote themselves”—the ones where I just kept finding the next part of the story.

STEP TWO: Search for pieces of the same story.

Once you’ve got an enormous pile (physical or digital) of songs, start seeking out a common thread. The theme that intrigues you most may not span a full album’s worth of material, but will still give you a place to start filling out the rest of your tracklisting. On rare occasions—like my second album, Millennium, written as a series of letters to one person—you may start writing from a determined concept, but I find this is a) an infrequent occurrence and b) can restrict the writing process as you prioritize composing songs that “fit” over songs that are rewarding to write.

I wrote the “The Ballad of Guinevere and Lancelot” in London as a sort of fairytale distraction from being quarantined with COVID-19; “Cleopatra’s Interrogation” followed upon my repatriation to America, provoked by my weekly Zoom readings with The Canon Shakespeare Company in Portland, Oregon. Once I had those two tracks side-by-side, I was struck by the reverence they revealed for legendary ladies—storied women that I’ve sought to emulate in my own life. I found actor Michael Sheen’s view that “myths are for… human beings to process their experience in extremis” remarkably prescient and started to untangle the fraught situations in my own life through the lives of women who went before me.

Pilgrim is the album I’m proudest of because it was written with the most love. I cared about these women’s stories, and in turn, trusted them to tell mine. The tracklisting for Pilgrim (below) includes the mythos surrounding Queen Guinevere, Joan of Arc, Una from Edmund Spenser’s “The Faerie Queen,” William Shakespeare’s version of Cleopatra, and Persephone.

STEP THREE: Curate, a team of people who are better than you are.

Here is a list of things I can do: write clever things, play some instruments competently; sing; basic recording and mixing; arts and crafts.

Here is a list of things I can’t do: read music; prepare arrangements, studio-quality editing.

As an artist, it is essential to hone as many skills as possible within your career field… As a human being, it is just as crucial to ask for help filling in your gaps. I self-produced Millennium because the intimacy that came with a home studio recording suited the album’s concept. Pilgrim was a whole different bunch of flowers: the stories were much more significant than any one woman, so I called in another legendary lady to help.

As you can see, my producer Anna Short is a saint. She received my lyric sheets and demo recordings and helped me turn them into magic despite my lack of technical proficiency and a five-hour time gap. I supplied her with the music, lyrics, and mood of a track, and she would develop arrangements and instrumentals to supplement them.

Anna offers this advice to prospective artists and producers: “My tip to anyone wanting to find a collaborator or producer is to put yourself out there and have conversations with people you already know. If they can’t help you, they might know someone! When you find the right person, you’ll know. Building an honest friendship with your producer that goes beyond the music will be beneficial to both of you. Develop a positive, honest, and humourous working relationship. Ensure your goals and ambitions are mutual and understood… The most important thing is the mutual creativity of the project. The rest will follow naturally.”

STEP FOUR: RECORDING.

While most albums production won’t occur across seas, with Facetimes during a pandemic, all albums will require some technical savvy. If you aren’t shelling out for studio time, you should have a decent home studio; mine is comprised of a RODE NT1-A Cartoid Condenser Microphone, a Focusrite Scarlett 2i2 interface, and my Macbook Pro. Once I had my tracks recorded on GarageBand and sent to Anna. She recorded additional tracks in her studio and mixed with Logic Pro X to my specifications (and sometimes live feedback, as evidenced below).

Each track was sent back and forth between us multiple times. I sent a demo; Anna sent a base track; I added vocals; Anna added orchestrations; I made notes; Anna made changes—all this until we both decided the track was the best it could possibly be. This is time-consuming and can be much less fun than making art without a deadline or any need for it to be “good.”

It’s so crucial that you remember why you are going through the sometimes agonizing process of listening to your own work so often you aren’t sure if you’re a real person anymore—focus on your duty to telling the stories you set out to tell. Like any producer worth her salt, Anna was a sage stress sponge during this time: “Making mistakes and getting things wrong is all part of the process, so never feel like you’re wasting time. You have to build the bridge to get the end goal.”

STEP FIVE: Cover your bases.

When you need a reprieve from recording, redirect to the other necessities of dropping an album. Who’s going to make your album art? Crafting together the unapologetically glittery and unflinchingly feminine covers for Pilgrim was such a joy that we ended up with artwork for each individual track—including this one for “xxx Dirty Girl”—which enabled them to be listed for download as singles in addition to their place on the full album.

Where are you distributing? Bandcamp was my first merchant because of its accessibility and artist-friendliness; it’s the digital music version of shopping local. However, because we knew Pilgrim had the potential to reach a broad audience, I made arrangements with a distribution company with the commercial rights to list the album on platforms individual artists don’t have access to without representation.

These small tasks together take up significant time, so don’t leave them waiting until the release date!

STEP SIX: Put yourself out there.

Pushing the “Publish” button on Pilgrim was difficult in a way I hadn’t experienced before. Anna and I knew she was a good record, and sending her out into the world is probably the closest either of us will get to sending a toddler off to preschool. But the stories were done, and they needed to be told.

There are rewards beyond album sales that come once your record has dropped: for one, I’m now a verified artist on Spotify—I’ve got the same blue check my heroes have!

If you optimize the tags on your listing platforms well, people you’ve never met will find your music from search engines and fall in love. Anna and I already have invitations to gig in London once venues re-open, sent from strangers who saw the same spark in Pilgrim that we felt making her.

If you’ve got a story to tell, people will listen. Hopefully, these steps give your storytelling some structure, but the biggest lesson I’ve learned from nearly a decade of making music is:

If it’s good art, you don’t know what you’re doing, because it’s never been done before.

Don’t be afraid of not knowing. Just tell your story as best you can—everything else is extra.

Pushing the “Publish” button on Pilgrim was difficult in a way I hadn’t experienced before. Anna and I knew she was a good record, and sending her out into the world is probably the closest either of us will get to sending a toddler off to preschool. But the stories were done, and they needed to be told.

There are rewards beyond album sales that come once your record has dropped: for one, I’m now a verified artist on Spotify—I’ve got the same blue check my heroes have!

Listen to Amanda’s music here: